European countries rely heavily on Russian oil and gas supplies, but the Ukraine crisis has caused the European Union (EU) and Britain to impose a series of sanctions on Moscow, including reduced imports.

In early March, the EU pledged to cut gas imports from Russia by two-thirds before the end of the year, while Britain said it would eliminate oil imports from Russia by the end of the year.

But these moves are considered quite risky for a region already facing an energy crisis.

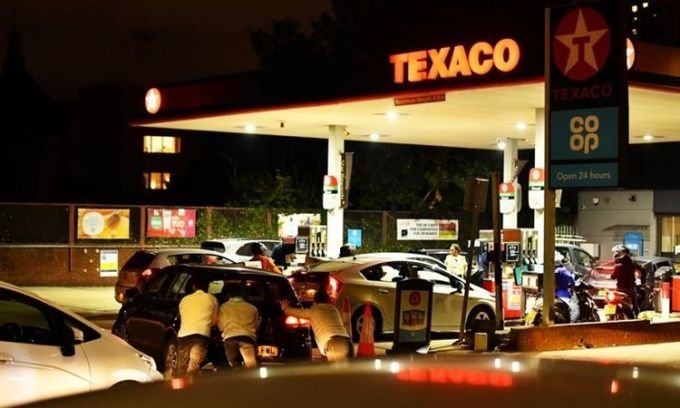

Vehicles lined up to fill up with gas in London, England, last September.

Germany on March 30 warned that the country may soon fall into a gas emergency and be forced to apply limits on gas distribution.

On the same day, the Austrian government announced that it had activated the first step in a three-phase emergency plan to control the gas market more tightly.

According to Chi Kong Chyong, director of the Cambridge University Energy Policy Forum, other countries in Europe are also likely to have to take emergency measures like Austria and Germany, if the West continues its `confrontation`.

Last week, Russian President Vladimir Putin said the Kremlin would ask `unfriendly` countries to pay for gas in rubles.

74% of Russian gas exports went to European members of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) last year, according to the US Energy Information Administration (EIA).

`Even though the weather is warmer and gas consumption is less, we still need to reserve gas for use in the coming winter months,` Chyong said.

According to Russell Hardy, CEO of Swiss energy and commodities trading company Vitol, in addition to gas, Europe also imports 50% of diesel from Russia and the remaining 50% from the Middle East.

EIA estimates Russia exported about 4.7 million barrels of crude oil per day in 2021, nearly half of which went to OECD countries in Europe.

Speaking at the British Parliamentary Budget Committee last month, Amrita Sen, research director at energy and macroeconomics consulting firm Energy Aspects, warned that sanctions on Russian energy could

`We are concerned that by the end of this month, Germany may have to implement a plan to impose limits on diesel,` Sen said.

Jim Watson, professor of energy policy and director of the Institute for Sustainable Resources at the University of London, said it was `almost certain` the British government would have to impose fuel limits on cars.

According to him, Britain has more difficulty weaning off Russian oil than gas, because the country is more dependent on imported oil.

Last year, a wave of gasoline hoarding in the UK led to a serious supply shortage, causing many gas stations to run out.

Watson warned that the situation this year is completely different, when supply is scarce because the UK proactively reduces energy imports from Russia.

According to Watson, to respond to the situation, the British government may have to implement policies to reduce people’s demand for gasoline, encourage them to use public transportation and change consumption behavior.

The International Energy Agency recently released a report outlining 10 policies that the agency believes will help quickly cut global oil demand by about 2.7 million barrels per day.

Some proposed policies include reducing maximum speeds on highways, reducing public transport fares, proposing car-free Sunday initiatives and circulating private cars on odd-even days in cities.

Rory Stewart, former British international development minister and senior fellow at Yale University’s Jackson Institute, believes that Britain can reduce energy imports from Russia by reducing domestic demand.

`But that requires a coordinated effort between the people and the government, like how we responded to the Covid-19 pandemic,` he said.

Stewart’s policy proposals include reducing the maximum speed in the UK to 80 km/h, making public transport free and calling on companies like Uber to open up technology to allow people to share personal cars with each other.

`This will reduce people’s demand as well as Russian oil prices, thereby affecting President Vladimir Putin’s policies,` Stewart emphasized.

Expert Chyong from Cambridge University also believes that the key for Europe to reduce dependence on Russian fuel is to focus on energy `austerity` policies, cutting down on the need for gasoline and gas.

`There is a negative relationship between demand and price, because we are facing a very tight energy system globally, any additional demand pushes up prices,` Chyong said.